|

The story behind Arnold Schoenberg's 1908 masterwork, his String Quartet No. 2, is as dark and brooding as the music. I thought I would share a bit about the background of this piece and my relationship to it, taken from my own observations as well as the writings of Alex Ross in his fascinating book on 20th century classical music called "The Rest is Noise."

In 1907, Schoenberg befriended the "brutal expressionist" painter Richard Gerstl, painting his famous self portrait under Gerstl's tutelage, and in May of 1908, Schoenberg discovered that his wife Mathilde was having an affair with his painting teacher. Mathilde and Gerstl ran away together and after a time Mathilde returned to Schoenberg, after which Gerstl staged a dramatic suicide on the night of a concert of Schoenberg's music that he had not been invited to. Schoenberg finished his String Quartet No. 2 the following summer. The first two movements seem to "hesitate at a crossroads, contemplating various paths forking in front of him." Then he turns to the poetry of German Symbolist Stefan George and includes a soprano for the last two movements titled Litanei (Litany) and Entrückung (Transcendence). The text comes from a large poem cycle George wrote in memory of a 16 yr-old boy who died of tuberculosis and whose death left the poet in "spams of grief." Litanei explores the pain of loss ("Kill the longing, close the wound!") as the soprano weaves with the quartet in surges of pain and confusion. Entrückung begins with alienation, with all that is familiar turning away from the poet, but ends in transfiguration ("I am but a spark of holy fire. I am but a roaring of the holy voice."). The piece is dedicated, you will note, "To my wife." This is Schoenberg on the brink of atonality, but still very much rooted harmonically and extending from the music of Mahler and Strauss. He moves through harmonic progressions quickly, so at times it seems like there is no harmonic center, but always we have chords and connections to harmony for our ears to hang onto, even if they are strange and less familiar. This quickly moving harmony only adds to the feelings of loss, confusion, and pain that Schoenberg (and George) are expressing. I first learned this piece for a performance at Tanglewood July of 2017. It had been on my list of pieces to learn for years, so I was so happy to have the space and opportunity to tackle such a challenging and stretching piece of music working with the great soprano Dawn Upshaw (an longtime mentor of mine) and cellist Norman Fischer (who coincidentally I had worked with as a young string player in NH). What I was most surprised by was how remarkably tonal it was, not in a "tuneful" way, but in a way that my ear could connect my melodic line as it reached and dipped with the string parts. The piece is a masterwork for many reasons, but mostly I'm struck by how innovative the string writing is. Schoenberg seems to capture the full range of grief in the colors, rhythms, textures, and articulations he chooses, and of course the harmony. In performance, this piece is truly a transforming experience both for the musicians and the audience. It is a journey of the soul in pain. After my first performance of it, I felt like I was still in another world for another couple hours after the concert was over -- it had that dramatic affect on me, particularly the experience of sitting on stage and listening to the first two movements searching and reaching before standing to sing my two contributions. The Aizuri Quartet is an incredible group of passionate, deeply feeling people and players, and they are truly a dream group to work with on any project, but particularly a piece of such magnitude and and depth. It is a great honor to bring Schoenberg's Quartet no. 2 to life with them and to share it with our Scrag audiences in Vermont.

3 Comments

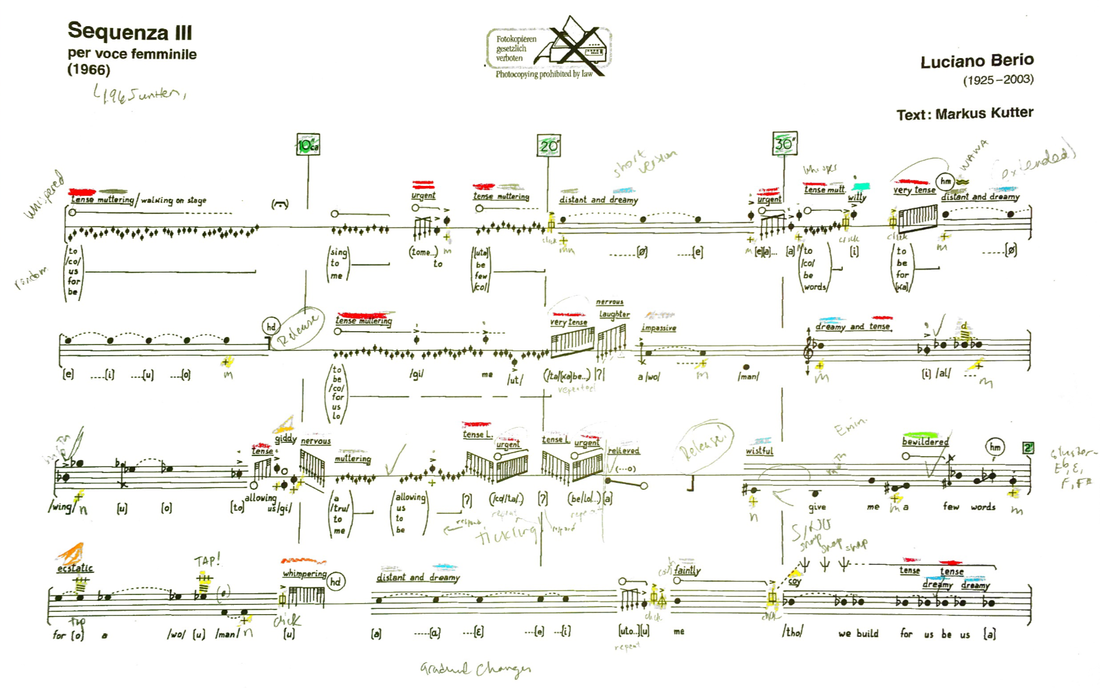

Luciano Berio was an Italian composer (1925-2003) noted for his contributions to electronic and experimental music. In 1958, he composed what is considered to be the first piece of electro-acoustic music involving the human voice for his wife (for whom he wrote all his vocal music), mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian. In that same year, Berio also began a series of compositions for solo instruments titled Sequenza I-XIV which explore virtuosity and extended techniques in short six to ten minute pieces. Sequenza III, which I will perform in our May 18-20 “Trapeze” concerts, was written in 1965 for solo female voice and for his wife who was known for her ability to shift moods and expression rapidly and also for her theatrical approach to experimental music. Each Sequenza is meant to push the musician to his/her limits of technique and expression, and Sequenza III is no exception! Of the piece, Berio wrote: “The voice carries always an excess of connotations, whatever it is doing. From the grossest of noises to the most delicate of singing, the voice always means something, always refers beyond itself and creates a huge range of associations. In Sequenza III, I tried to assimilate many aspects of everyday vocal life, including trivial ones, without losing intermediate levels or indeed normal singing.” http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1460?1487325698=1 The piece itself is structured around a modular text by poet Markus Kutter: Give me a few words for a woman to sing a truth allowing us to build a house without worrying before night comes The "poem" is meant to be read any way - across, diagonal, down – with the meaning changing significantly depending on which way it is read. We can think of this as the original refrigerator magnet poetry! I.e. 1 Give me a few words for a woman to sing a truth, allowing us to build a house without worrying before night comes. I.e. 2 Give me a truth before night comes to build a house, truth for a woman to sing, allowing us a few words without worrying. Instead of setting the text in the way the poem was meant to be approached, however, Berio was curious about how the sounds of the words contribute to the meaning we attach to them. He broke the sounds of each word apart from the word and the meaning and inserted his own emotional directions into to how to sing and interpret each word. The listener will rarely hear distinct recognizable words, but there are enough hints to keep the connection to the poem and the feeling of longing for self-expression that I read in the original. If you take a look at this crazy score, you can see how Berio uses words (often in parentheses), phonetic sounds (with dashes surrounding them as in /wo/ /man/) and also sounds in IPA, the International Phonetic Alphabet that is used by linguists and singers as a systematic way of communicating pronunciation of individual sounds, for examples [i] is pronounced "eeeee" as in the word "see." Language and the feelings that different sounds evoke definitely become the focus of this piece. From the score, you will also see how there are very few pitches written out on the musical staff. There are sections like this where pitch is specific, but most of the sections are either not specifically notated on any staff, or a limited staff of three lines to indicate low, middle, and high points of the voice. This can be sung by any female voice, low, medium, or high, and is endlessly adaptable. Lastly, on the score, you can see how I color coded it to make it easier for me to interpret the emotional instructions (red = high intensity emotions like "intense" or "desperate" vs. mellow ones = blue like "dreamy" or "peaceful" or "wistful". Besides the challenges of quick changes in emotional state/vocal color/intention, there is the additional challenge of learning to interpret the symbols Berio uses to indicate: a cough, a click, finger snaps, covering the mouth, tapping the mouth…etc. Much of my practice time in learning this piece has been spent learning these symbols and being able to interpret them fast enough to do them in the context of the music. A fun challenge to say the least! To be honest, I have been putting off learning this piece for quite a few years now because of its technical and physical demands, the vulnerability of singing a cappella (with no accompanying instruments or voices), and the weight of its importance in the history of vocal music. I began learning it a few years ago, then put it away until last fall when I started learning it in earnest again. Berio writes that Sequenza III is a "dramatic essay whose story is between the soloist and her own voice." In some ways, that is terrifying because it becomes such a personal piece for each singer (each singers' interpretation of what "tense" or "dreamy" or "nervous" or "bewildered" will be so unique), but in other ways it is incredibly liberating for the same reason. For much of the repertoire I sing, there are expectations about "how" I will be singing it. Not so with this piece. I am able to craft it in a way that is authentic to my own dramatic expression and the strengths and limitations of my voice. Although scary and challenging, when done well Sequenza III is an extremely funny and fun piece of virtuosic vocal music. Sound is play! This piece is all about playing with what the voice can do and how language is created, and emotion from the language or vice versa. There is no specific narrative except the drama of the singer and her voice at play. What could be more delightful than that?! --Mary Bonhag |

Inside the Music with Evan Premo and Mary Bonhag.A space to share some further thoughts on music. Comments, questions, and discussions are encouraged. Archives |